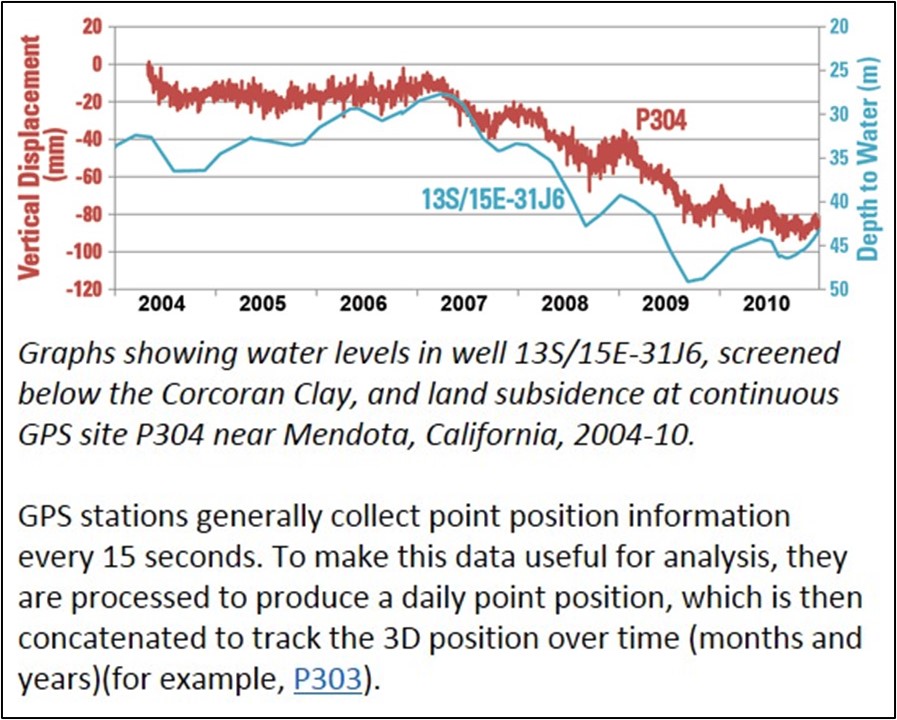

An underestimated risk factor

In the chapter “Climatic Conditions” of the K.A.R.L. reports, there is a parameter that has been listed from the beginning, but which has probably been overlooked by many due to its inconspicuousness. Yet under the weather conditions of the last few years it has increasingly made headlines in the media and is gaining in importance: water availability. This newsletter will take a closer look at what this is all about.

Withered meadows, danger of wildfires and rivers that have melted down to a fraction of their normal water flow. Shipping is affected because the navigation channels are no longer deep enough, and power plants have to reduce their output because there is no longer enough river water for cooling. These are topics that have increasingly dominated the headlines in the summers of recent years, at least here in Central Europe. Elsewhere, the worries are many times greater. California, for example, is repeatedly suffering from droughts that have now reached catastrophic proportions. Many farms are on the verge of going out of business, wells are dry and drastic water-saving measures are being imposed on the population.

Whether Cologne or California, the issue is the same: There is less water available than needed. What constitutes “water availability” in a region? And above all: what economic consequences for the industry can result from water scarcity?

Water availability is an issue that concerns not only private consumers or agricultural businesses. Many industrial companies also maintain their own wells from which they cover their service water needs for production, cooling of aggregates or for extinguishing water and sprinkler systems. Such wells draw on local groundwater reserves. However, if these regenerate too slowly or run out completely, entire industrial sites can be affected. They may then have to change production or even relocate.

As a pioneer in a newly designated industrial zone, one will not notice any of this yet. Only when several businesses have been utilizing groundwater for years in succession, and the water reserves deep underground have been diminished to a meager reminder, does the scarcity become evident. The minor issue in this context is that nowadays, air conditioning systems are also increasingly being operated in an environmentally friendly manner using groundwater.

However, not only industrial sites themselves can be affected, but also the infrastructure in the surrounding area is dependent on regional water availability. To ensure smooth transportation of raw materials and removal of finished products, waterways should rarely have low water levels, otherwise production will come to a halt. Production stoppages or disruptions in the transport of goods can also occur if energy suppliers partially or entirely fail due to the cooling water demand no longer being met.

In addition, water scarcity can destabilize social structures, incite unrest and lead to revolutionary upheavals. Quite a few scientists even argue that the wars of the future will be fought predominantly over dwindling water supplies. Water availability is thus a factor that must also be taken into account in the analysis of political risks. There are, therefore, many reasons to delve deeper into this topic and its scientific background.

Where does the water come from and where does it go?

All water on earth is part of a constant cycle. It evaporates over the sea, travels with clouds over the land, falls as rain, seeps into the ground, is being collected, evaporates again, or flows back into the sea through streams and rivers. Sometimes this cycle can happen quite rapidly. However, when water sinks deep into groundwater reservoirs or ends up in the eternal ice of glaciers, the cycle can take thousands of years. Therefore, only the branch of the water cycle that remains close to the earth’s surface and neither evaporates nor seeps too deeply is immediately available to humans and nature.

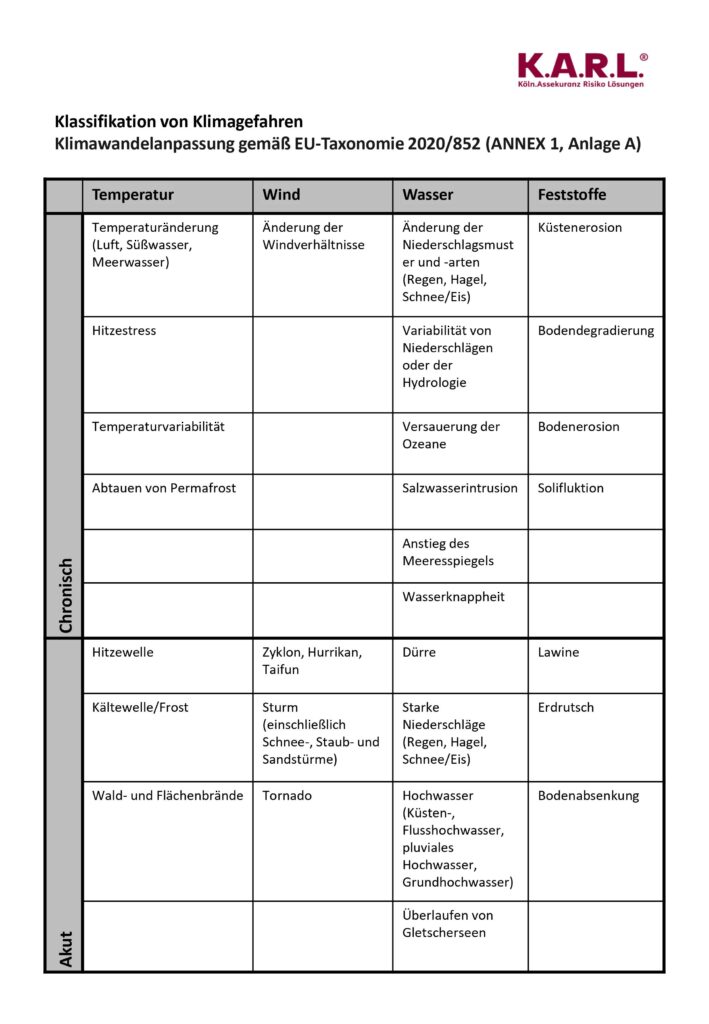

Using formulas from hydrogeology, it’s possible to calculate from the annual precipitation and the average annual temperature the proportion of effective evapotranspiration, i.e., the amount of water that can evaporate under these conditions each year. If this value exceeds the annual amount of precipitation, theoretically, there is nothing left that could flow, seep, or be collected. This exact situation is found in the desert areas of the earth, where water essentially evaporates faster than it can fall from the sky. These areas are highlighted in yellow in the following map below.

Fig. 1 Calculated water availability in Europe.

In large parts of Central Europe, the map shows shades of blue to deep blue. These indicate that there, usually, more than 200 mm of annual precipitation do not succumb to evaporation and are theoretically usable. Concerns about water supply don’t need to be fundamental in these areas. At most, during extremely hot summers, temporary low water levels in rivers might occur. The well-known consequences for navigation, however, typically become part of the past within a few weeks.

However, the situation becomes critical when water availability falls below 150 mm per year. In such cases, as in southeastern Italy or parts of Greece and Turkey, significant water scarcity can persist for weeks or months. Even in southeastern England as well as in certain areas of eastern Germany and Poland, complaints about extreme and prolonged drought are heard from time to time.

Less than 50 mm of annual precipitation is available in many regions of Spain. As the map reveals, desertification has already set in in some areas. In satellite images, Spain’s grayish-yellow color distinctly contrasts with the otherwise predominantly lush green of Central Europe.

Fig. 2 Satellite images, source: Google Earth.

In North America, an almost razor-sharp border separates the water-rich east from the arid west. Especially the border region between the USA and Mexico is predominantly desert-like. In the lee of the coastal mountains, this desert strip extends far northward, with its last fringes reaching almost up to the Canadian border. Water abundance comparable to Central Europe is only found in the narrow mountain ranges along the Pacific coast itself. The colouring of the satellite images reflects these conditions and confirms the calculated water availability.

Fig. 3 Calculated water availability in the USA.

Fig. 3 Calculated water availability in the USA.

California’s Central Valley, the fruit garden of North America, also actually belongs – at least in its southern part – to the desert regions. Nevertheless, the valley floor in the satellite image shows a lush green that contrasts sharply with the sand-coloured mountain slopes in the surrounding area. How is it possible that here, at least seen from space, abundant vegetation thrives? What is the difference between the greenery in Central Europe and that in the California valley? Or, what separates our relatively mild summer dry periods in Central Europe from the extreme drought that California has been grappling with for some time?

A comparison of climate conditions and, above all, climate trends over the past decades can provide answers to these questions. For this purpose, weather data from two observation stations in Central Europe and California were used as examples.

Drought in two variants – Germany and California

As a representative example of the water-rich areas of Central Europe north of the Alps, the weather station at Cologne-Bonn Airport (DWD-02667) was evaluated for the years 1970 to 2015: Despite the fact that there has been a significant increase in mean annual temperatures from 9.5 °C to 11.0 °C since 1970, the calculated water availability has remained at about 300 mm per year on average. Although there are extreme jumps between 100 mm in the dry year 1976 and over 500 mm in the early 1980s, the water availability does not show a long-term declining trend, as might have been expected due to the rising temperatures. This is mainly due to the consistently precipitation levels between 600 and 1000 mm per year, which mostly compensates for evaporation losses even in hot years. Of course, there are exceptions where this hasn’t worked as well, such as in 1976, 1996 or 2003. However, such downward “outliers” have always been balanced out by an excess of water in the subsequent years. Therefore, with all due caution, it can be assumed that this is likely to continue, and Central Europe will not permanently fall below the critical threshold of 200 mm of water availability in the foreseeable future. At worst, there might be a few isolated dry years to endure. However, due to the temperature increase, these could occur somewhat more frequently in the medium to long term.

Fig. 4 Evaluation for Cologne-Bonn, data source: DWD.

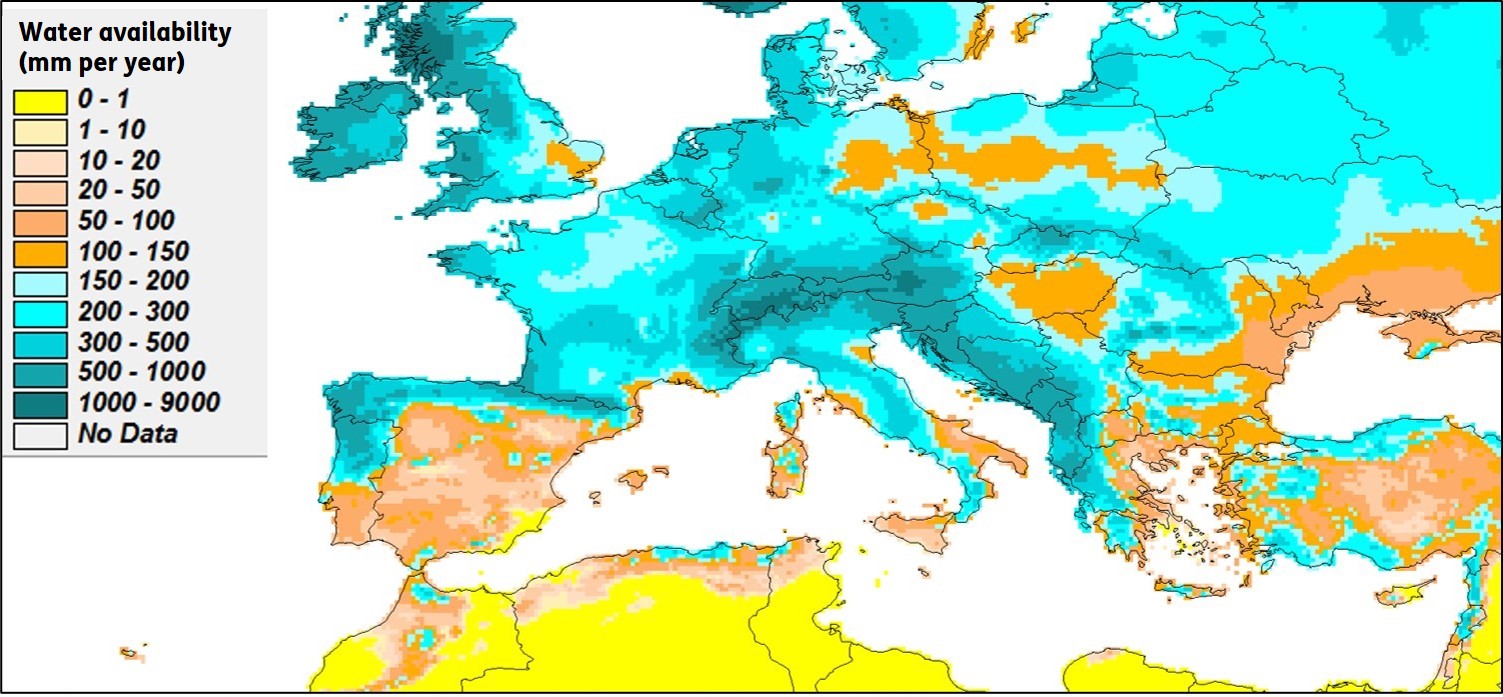

In contrast, the situation in the Californian capital, Sacramento, located in the northern part of the Central Valley (Station: NOAA-724830), is quite different. Although the temperature increase since 1970 has been rather moderate compared to Cologne, at around 0.5 degrees, the annual mean temperature is currently 16 °C, which is 5 degrees higher than in the Rhineland. Therefore, the overall evaporation rate in California is already significantly higher than in Central Europe. If only that were the extent of it, California would probably have somewhat fewer concerns today. Unfortunately, in addition to this, a pronounced decrease in precipitation levels has occurred since the 1980s Back then, there were still individual years where precipitation amounts of 1000 to 1300 mm could be measured. However, since the turn of the millennium, annual rainfall has consistently remained below 600 mm. On average, rainfall amounts have decreased by about 30 percent over the past 40 years. This is a trend that, given the generally prevailing temperatures there, has catastrophic long-term effects: The calculated average water availability, which was around 100 mm per year in 1980, and not exactly abundant to begin with, has now dropped to around 35 mm. The long-term trend even points towards zero. In hindsight, it was foreseeable from 1990 onwards and, by the year 2000, almost a certainty. Therefore, it cannot be argued that the current drought is an unexpected occurrence.

Fig. 5 Evaluation for Sacramento, data source: NOAA.

So why is it still green and blossoming in the Central Valley – at least at the time the satellite image was taken in 2013? The solution to this puzzle lies in the use of groundwater reserves to irrigate the fields and plantations. Geologically, the Central Valley is like a huge subterranean bowl whose rising edges are formed by the mountain ranges that surround the valley. The available portion of the precipitation that falls in the area of this bowl collects there, seeps away and remains in the soil as groundwater. Unfortunately, however, much more groundwater is currently being extracted for the irrigation of agricultural land than is supplied by the rain that falls in the valley itself and its narrow peripheral mountains. Furthermore, two trends have been conflicting here for years: water availability is decreasing, while groundwater consumption is simultaneously increasing.

The dire consequence is that the groundwater level is declining more and more, and the wells can no longer reach it. They are literally running dry. New wells must be drilled or existing ones deepened. Well drillers are currently in high demand in California.

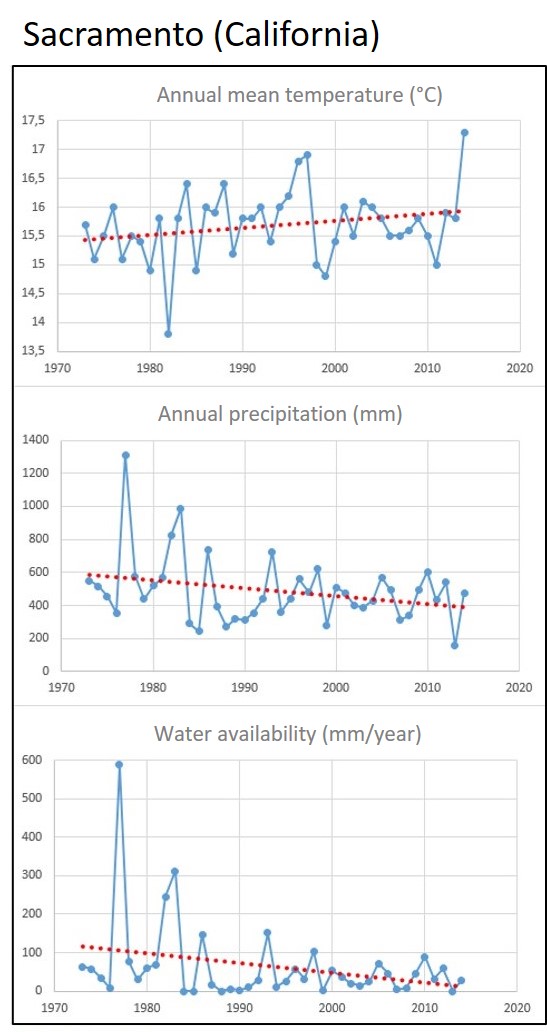

And there is another unpleasant side effect of the drought: the cavities left behind by the groundwater in the subsoil are collapsing. This not only reduces storage space for potential future groundwater if it were to rain more again, but it also causes the land surface to subside by the amount that the now compacted storage rocks in the subsurface have lost in volume.

Fig. 6 Falling water table and land subsidence at Mendota (Central Valley), Source: USGS

However, it becomes extremely concerning when the water needs of industry, agriculture, and private consumption are drawn from so-called fossil groundwater reservoirs. These are groundwater sources that were formed during earlier, more humid climatic periods, such as the last ice age around 25,000 years ago.

Such groundwater reserves, found in places like the Middle East, beneath the Sahara Desert, and in the Midwest of the USA, no longer replenish themselves under today’s climate conditions. Once they are depleted, they are empty and remain so. Permanently.

Conclusion

All of this—and several more complex interconnections and cross-links—underlies the parameter of water availability that K.A.R.L. has been reliably calculating for years and includes in its reports. However, the consequences don’t always have to be as dramatic as in California or as reassuring as in the Rhineland.

When K.A.R.L. calculates a water availability of over 200 mm per year, there can generally be a sense of relief. Even under unfavorable geological conditions (where rainwater quickly runs off steep slopes into streams and rivers or disappears into deep crevices and caves, like in the Croatian karst mountains), ensuring water supply is not an insurmountable problem: Water might be somewhat more challenging to extract or retain, but at least it’s present. In such cases, K.A.R.L. issues the following statement:

“In the present case, a value of 200 mm per year is exceeded. A water shortage is therefore not to be expected, except in extremely hot and dry years.”

However, if K.A.R.L. issues a notice like the following, and if long-term reliance on a secure water supply is necessary, further exploratory measures should definitely be initiated:

“In the present case, water availability falls below a value of 50 mm/year. Against the background of global climate change, there is a high risk of drought. Considering the global climate change there is a latent danger of aridity. The situation requires supervision.”

Further actions can include, among other things, more precise analysis of climatic developments (as demonstrated in the examples of Cologne-Bonn and Sacramento), or detailed exploration of regional geological and geographical conditions. If the latter are unfavorable, as in the Californian Central Valley, even minor climate changes can lead to catastrophe. Conversely, if they are relatively favorable, such as in Egypt where the Nile, in a desert environment, consistently provides a relatively continuous water supply “from outside,” the K.A.R.L. warning can be mitigated. Nonetheless, in any case, it is advisable to examine the facts more closely under such conditions and potentially consult specialists in water management, engineering, and hydrogeology.

So, it’s worth taking a look at what K.A.R.L. has to say in its reports on water availability and, if in doubt, conducting further investigations. This is especially relevant considering that, as part of global networking, industrial companies are increasingly venturing into regions that significantly differ from the manageable and familiar conditions in Central Europe. Incurring additional problems due to gradually emerging water scarcity or facing social unrest triggered by it is the last thing internationally operating companies want to deal with.

If you would like to discuss this paper with us, we look forward to hearing from you.